About The Song

It’s a tale of two torch songs. The original, written in French as “Les Feuilles Mortes” (literally, “Dead Leaves”) was a dark lament of lost love and regret. The translated version, “Autumn Leaves,” touched on the same theme, but in a gentler, more wistful way.

The song began its life in 1945 as a poem. It was written by screenwriter and Left Bank intellectual Jacques Prévert as part of the script for a ballet called Le Rendezvous. Two years later, when director Marcel Carné made a film of the ballet, a Hungarian-born film composer named Joseph Kosma set Prévert’s poem to music. Maybe because the words weren’t conceived in song form, it took on a slightly unwieldy structure. Kosma interpreted it as 24 bars of introductory verse containing two distinct moods and melodies, followed by a 16-bar refrain (half the length of a traditional Tin Pan Alley song).

Carné’s film flopped, but the lead actor, a popular young singer named Yves Montand, took a liking to “Les Feuilles Mortes.” Though he didn’t sing it in the picture, he added it to his concert repertoire. At first, it was received coolly. No beat, an over-complicated structure, a relentlessly sad message—it had everything going against it. Montand kept singing it. Within a few years, it became his biggest hit and most requested song.

While the song belongs to Montand, there was another memorable version by French chanteuse Juliette Greco. The stunning, perpetually black-clad “Little Miss Existentialist” recorded it several times but, as with Montand, her early versions are best. With her smoky voice and languid phrasing, she brings an especially erotic spin to it, conveying the sense that she will never again love so intensely.

In 1950, when the song was finally translated into English, only a small part of the opening verse survived (and that was rarely sung). Mostly, it became about featuring the catchy, spiraling 16-bar refrain. Lyricist Johnny Mercer did create a few striking images—“the sunburned hands I used to hold” and “Old Winter’s song”—but in effect, this was a completely different song from the rambling elegy Prévert and Kosma had created. While the original was about an all-consuming passion, this was more about a fleeting attachment. More nostalgic than angst-ridden, more bittersweet than bitter.

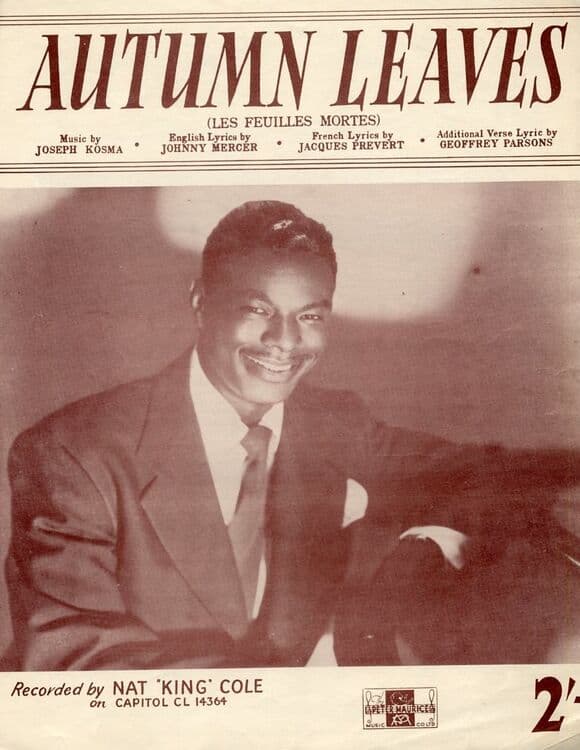

After Nat “King” Cole took it to No. 1 on the hit parade in 1955, it made the rounds as standard fare for nightclub singers—from Frank Sinatra (his 1957 recording on Where Are You? is appropriately dirge-like) to Tony Bennett to Eartha Kitt. Chick Corea, Stanley Jordan and Leonie Smith have all cut recent versions.

Video